By Rob Nightingale

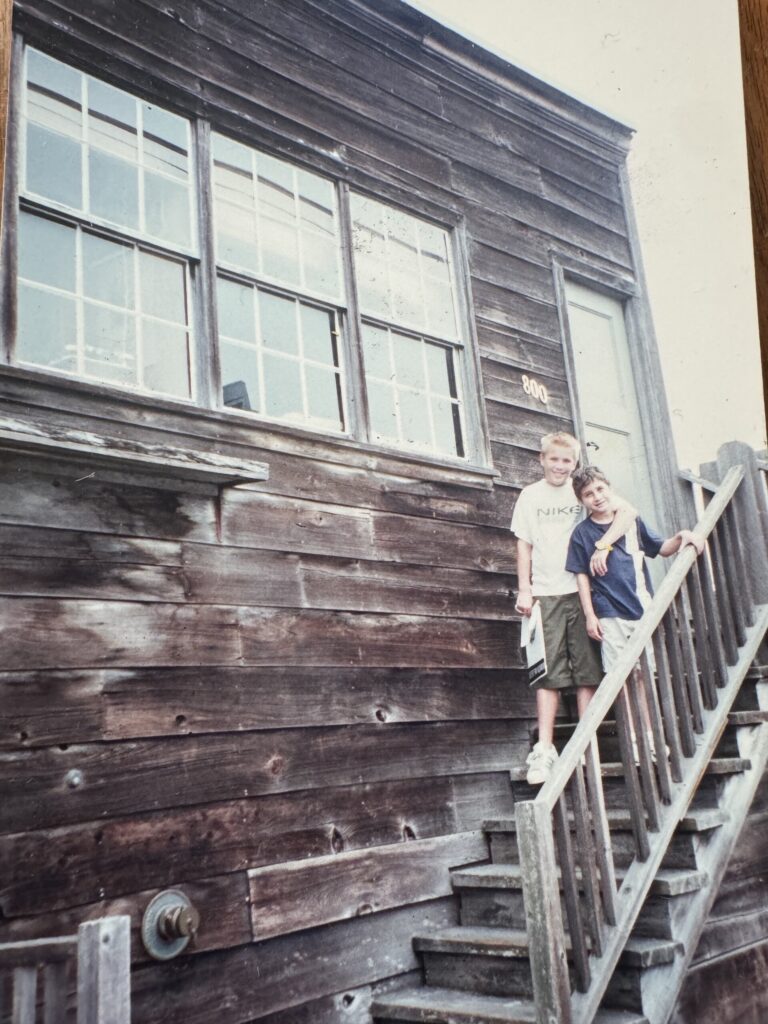

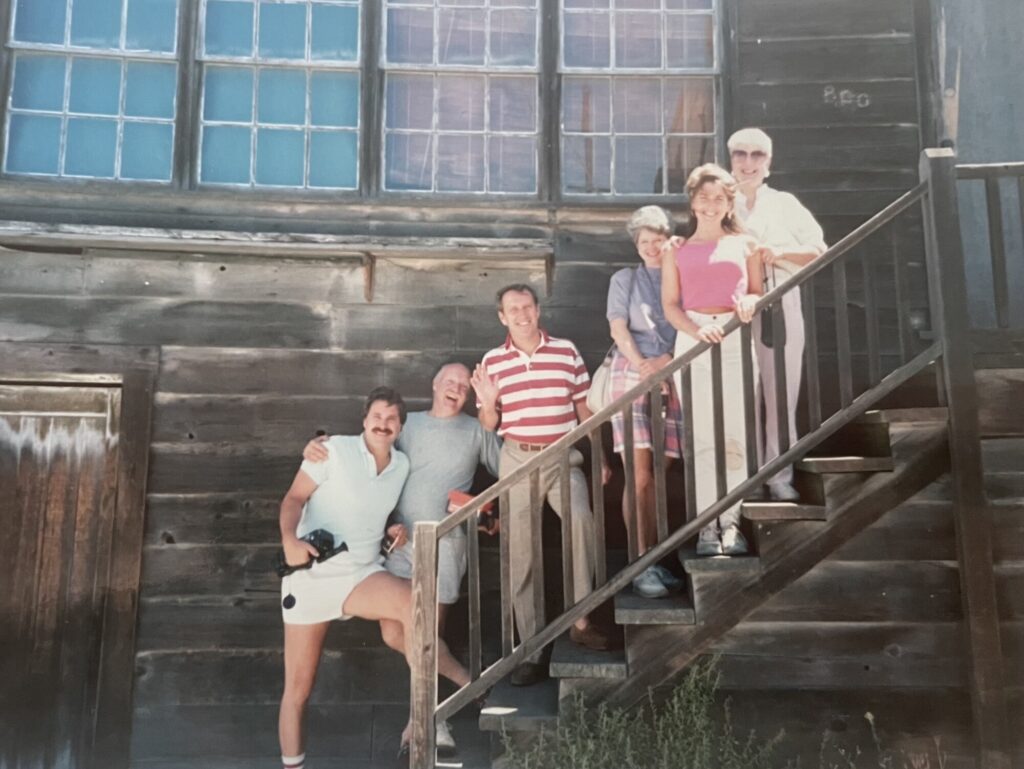

I was only six when I first creaked up the old wooden stairs into Pacific Biological Laboratory on Cannery Row.

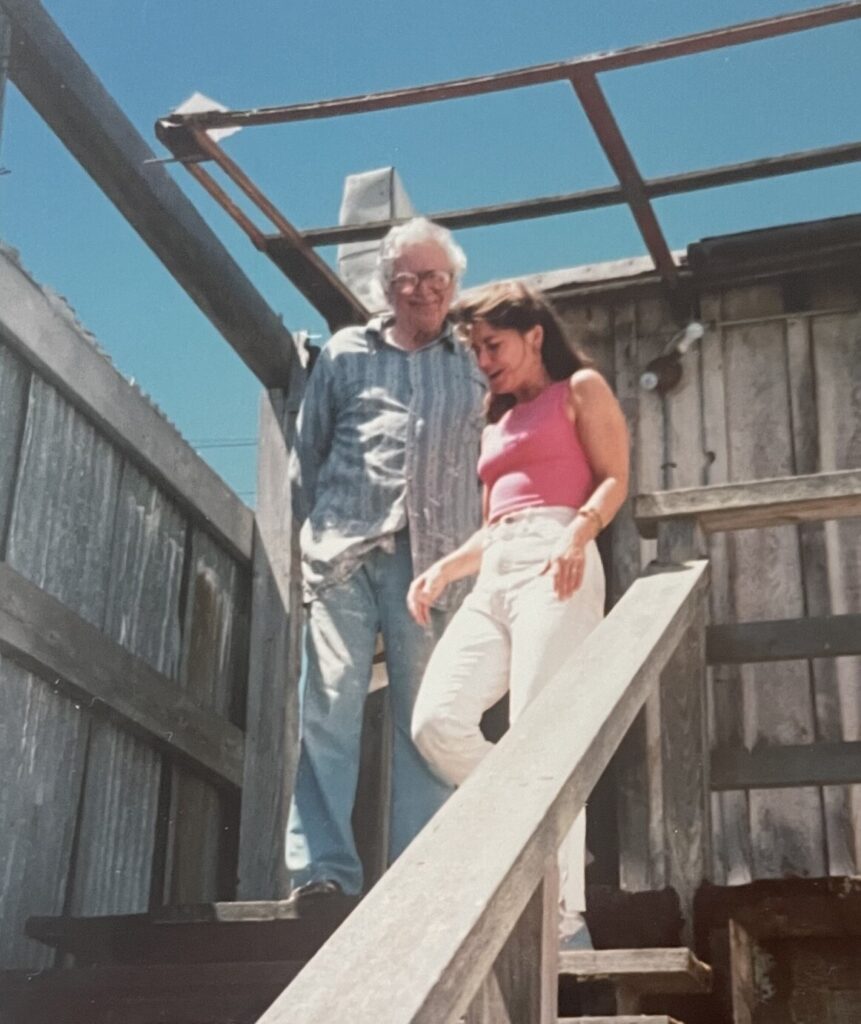

My Aunt Stacey had befriended legendary Monterey artist Bruce Ariss and he had given her the keys, allowing us a private tour of “Doc’s lab” decades before it was open to the public. Much like Ed Ricketts, Aunt Stacey was a teacher of all things science, ostensibly to middle schoolers in Carmel but, as Steinbeck said of Ricketts, she “taught everyone without seeming to.”

At six, I was just old enough to still retain some dusty memory of specimen jars filled with floating wonders, just young enough to have no concept of who the heck this Doc guy was.

My only points of reference for “Doc” were Bugs Bunny and my pediatrician. Though young, I was wise enough to know that Bugs Bunny didn’t live in an old house in the middle of Monterey. He lived in Manteca. So, I didn’t see what all the hubbub was about.

The second Stacey turned the key and opened the door, that changed.

I felt we were entering hallowed ground. We had just seen whales, otters, rays, sharks, and jellyfish at the world’s premiere aquarium not twenty minutes prior, yet it was here where my mother and father’s voices hushed. Far from the crowds, in the quiet cozy room insulated with records and books, old photographs and jazz posters, jars of preserved octopi and sea stars, my parents’ eyes drank with wonder the simple sites and whispered with sanctity the names “Ricketts” and “Steinbeck.”

I couldn’t understand it. Who was this “Doc,” anyway? I didn’t see any medical instruments.

“Well, he wasn’t that type of doctor,” my Aunt Stacey explained.

“He was someone who loved learning. He was endlessly curious, just like you,” she said.

“He made his living sifting through the tide pools, just like we did this morning. He’d bottle up the animals and sell them to schools so people could study them and learn,” she said.

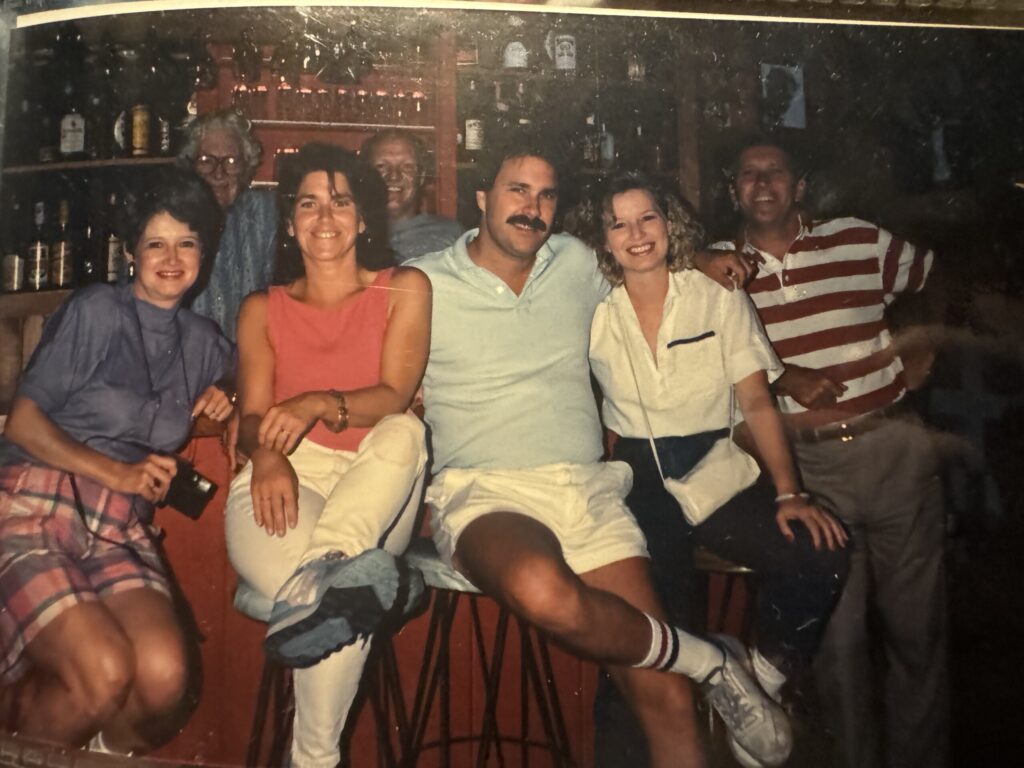

“He was nice to everyone he met. He taught them all the things that he knew, at least he tried to, and he threw great, big parties where everybody danced and listened to wonderful music and talked all night long about science and literature and art and history, about anything and everything they could think of. And everyone ate delicious food fresh from the ocean and laughed and laughed and laughed.”

Suddenly, I knew what I wanted to be when I grew up. I wanted to be just like Doc.

I laid on the tiny bed and let the soft sounds of the surf wash over me, the salty breeze blowing through the back door, turning everything it touched into magic. What once was drab and old was now historic, beautiful. Sacred.

Though the memory is hazy, the feeling of calm reverence has lasted a lifetime.

I grew up mythologizing Monterey. My father was born and raised in Pacific Grove. His parents, whom I never had the pleasure of meeting, worked in the Grove Laundry. Grandmother was the face of the front office while Grandpa Bud delivered fresh dry cleaning to half the peninsula’s residents, including John Steinbeck on occasion. He even held an intellectual conversation or two with him, according to family lore.

Living three thousand miles away in hot, sticky Florida, my brief and infrequent summer trips to the peninsula were heavenly respite. The cool fog fell over me, warmed my soul like one of Grandmother’s knit blankets. I would spend hours combing the tide pools with Aunt Stacey, watching the scenes beneath the glassy water like television, hermit crabs scampering through flowing fields of kelp, anemone tentacles dancing their patient dance of death, starfish feeling their way forward on their nearly blind hunt, and stoic urchins still amidst the chaos, venomous spines thrust forth like tiny spears from a miniature Macedonian phalanx.

Here for me was everything the warm, placid Atlantic beside those soft sand Florida beaches was not. Here, beneath the cool grey sky, on these rocks filled with the furious foam of the Pacific, where, as Steinbeck said, “the smells of life and richness, of death and digestion, of decay and birth, burden the air,” I felt one with all around me. The sea, sand, rock, wind, plants, and animals all merged into the elusive oneness that Ed Ricketts so often espoused. Here, where my father’s parents had raised their little family, where John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts and Joseph Campbell and Robert Louis Stevenson and so many others had found their inspiration, I came as close as any child could to “breaking through,” as Ed would say.

When I was old enough, and perhaps even a little before that, my father introduced me to Fila de conservas, Steinbeck’s semi-biographical novel that had sparked hordes of tourists to descend upon the street formerly known as Ocean View Avenue. I fell in love instantly.

Every time I visited my aunt in PG, I came with a Steinbeck in hand and more often than not, it was Cannery Row. Every time I read it, I was filled with a sense of connection to the street I’d walked so many times, the laboratory that held such a fundamental memory of my childhood. All the characters seeped into me, felt like old friends. Every time I finished, I couldn’t wait to start it again, to laugh along with Mack and the boys in their scheming, to revisit Doc and his quiet, lonely wisdom. It was my father’s favorite book. It reminded him of home. Now, it was mine too.

My love for literature, sparked by that trip to Doc’s lab and Fila de conservas led me to study Creative Writing in college and later to teach middle and high school English. Many times now, I have led students through the study of Steinbeck to my great joy, passing on to a new generation the love for Fila de conservas that my father gave to me.

Another year passed. Thomas and I were looking for a creative project to work on together. Separated by the length of the continent, we longed for connection. I’d written several scripts that had garnered some attention at this point, so we decided to write a screenplay together.

We lost my father in November of 2020. It took nearly two years to coordinate, but finally family and friends met in Pacific Grove and at sunset, we scattered his ashes into the sea beneath a bench dedicated to the memory of my grandparents. The next day, my brother Thomas was married beside the same bench.

It would be a fun, stimulating way to stay in touch. I proposed an adaptation of Cannery Row. This would honor the place of Dad’s birth, the place he loved, and hopefully help us to grieve, even if no one else ever laid eyes on the script.

Thomas agreed and we arranged to meet in Monterey the following February to begin.

As many of you may know, Fila de conservas has already experienced a film adaptation. After one failed adaptation attempt immediately following its publication in 1945, Steinbeck’s funniest book was finally brought to the screen in 1982. Since this film combined Fila de conservas with its Broadway destined sequel, Sweet Thursday, Thomas and I decided to go another direction. We would integrate Fila de conservas into the nonfiction Tronco del Mar de Cortés.

In our adaptation, Steinbeck would read the Fila de conservas manuscript to Ricketts while on their Western Flyer voyage, asking Ed his blessing for the novel that used his likeness for its sad, mysterious “fountain of philosophy and science and art,” Doc. Anachronistic, yes (Fila de conservas was not written until 1944, four years after the Mar de Cortés trip), but we felt the interesting framing device it afforded was worth the historical inaccuracy.

Somehow, I had never read Mar de Cortés. I had read Fila de conservas obsessively since I was twelve, known it even longer. I had read biographies of both Steinbeck and Ricketts, learned much about their legendary friendship, toured Ed’s lab multiple times, taught Steinbeck in my classrooms, and yet I’d managed to go without reading this wonderful work of nonfiction, this work of truth – truth, which Ricketts so loved. Steinbeck once said that Mar de Cortés was his favorite of his own works. So, I eagerly accepted my mission and dove into its warm, welcoming waters.

As I read, the trip bloomed across my mind like the brilliant fuchsia of summer ice plant. Every word leaped off the page, floored me with its wisdom and tenderness. Here was a collaboration between two monumental intellects, far-reaching and fearless as they were gentle and kind. Steinbeck and Ricketts’ words became my therapist, my priest, my surrogate father coaxing me through my grief with the noble reassurance that I should not concern myself with “what should be, or could be, or might be, but with what actually ‘is.'”

“The tide pool stretches both ways,” they told me, “digs back into electrons and leaps space into the universe and fights out of the moment into non-conceptual time. Then ecology has a synonym which is ALL.”

This deeply important scientific and spiritual truth is particularly profound when one is grieving the loss of a loved one thousands of miles removed from family. There is an interconnectedness to all things, biological or otherwise. Animated with the breath of life or recently reduced to ash and dust, we are all part of the same system, all made of material forged in the same celestial crucible billions of years ago. “All things are one thing and one thing is all things.” Steinbeck and Ricketts’ words reached out through “non-conceptual time” to provide me that solace. I am forever grateful.

Once I reluctantly finished the book, sad to see it end, Thomas and I again met in Monterey.

Each day, we split our brief time together between the lobby of the Monterey Plaza Hotel on Cannery Row and my aunt’s house in Pacific Grove. Each night, after writing all day, we would stroll from Stacey’s down Sinex to write some more beside the warm, crackling fire in the Asilomar Conference Grounds social hall.

During a break on the second day of marathon writing, Thomas and I were made aware of a fact many of you may already know. Aunt Stacey treated us to a drive through the Santa Lucia mountains to Salinas and the National Steinbeck Center. There, we stared at a map of California labeled with significant Steinbeck locations. Right on the edge of that little bear head Monterey peninsula was marked:

“Asilomar Conference Grounds – Where John Steinbeck wrote Sea of Cortez.“

We were stunned. Somehow, this fact had escaped us. To my brother and I, Asilomar was just a lodge down the street from my aunt’s house, a warm and quiet place to write. Please forgive us our ignorance, Steinbeck scholars and superfans out there, but at this point in our process, we were completely focused on the texts themselves and had done minimal research.

We rejoiced.

It felt as if we had unconsciously channeled the spirit of the text, connected with some sort of source energy left behind by its power that attracted us to the place of its creation like a magnet. This was just the beginning. At every turn, it seemed as if John was winking at us from beyond the grave, acknowledging we were on the right path, urging us to continue.

We finished the first draft of the screenplay in three sleepless days and nights, all the time we were able to take away from our other responsibilities. Exhausted, Thomas and I flew back to St. Augustine and Seattle, respectively.

Once we arrived back home, tucked into our opposite corners of the country, the true work began. We settled into ruthless revisions as we whittled our original 181-page first draft down to 120 pages, killing countless darlings along the way (though never Mack’s beloved pup, Darling. Rest assured, no fictional animals were harmed in the making of this screenplay, excluding Doc’s countless specimens).

After several months, we finally put our pens down and declared the script finished (for now).

I was in deep need of rest and relaxation. As Jones says in Fila de conservas, “nothing rests you like a good party.” So, I exited my months-long hibernation and retreated into the dense Douglas-fir and snow-capped peaks of Washington’s Cascade mountains to camp with friends for the weekend.

I procured party materials, cigars to celebrate, steak to fry over a bed of coals, plenty of whiskey, and a special bottle of liqueur, shaped like a nude Incan goddess, distilled only in Baja, regaled as an aphrodisiac, and lusted over by John and Ed on their Sea of Cortez expedition. Damiana.

When it was my turn to reveal what I’d been up to, fire crackling, bats squeaking overhead, lake lapping against rocks, I presented the bottle, lit the cigars, and told of my script. When I finished, one friend sat strangely silent.

Now, this man is very rarely silent. He is what is often referred to as “a talker.” He seems almost out of another era, wiry muscles forged over years in the shipyard, tobacco-stained teeth always laughing at some crass joke. When I needed to channel Cannery Row’s lovable tramp Mack for dialogue or mannerisms not already provided by Steinbeck, this man was my muse. His name, like mine, is Rob.

To find Rob silent was like finding yourself in a silent forest on a moonless night, deeply unsettling.

Finally, he spoke.

“Did you say the Western Flyer?” he asked with his gravelly, sing-song voice.

“Yeah. Do you know it?”

He swirled his Damiana, flickering flames reflected in proud, mischievous eyes.

“Hell of a boat.”

He puffed his cigar, then puffed out his chest.

“I worked on that sumbitch. Put the engine in myself. Mast too.”

I stared across the fire in shock. He grinned, cigar dangling from cracked lips, threw back the last of the golden amber liquid and savored the sweet sting.

“Now she purrs like a cat in heat.”

It turned out that as I’d been cooped up at home toiling away on the Cannery Row script, Rob had been working alongside Chris Chase installing the new hybrid engine for the Western Flyer less than two miles away on the Fremont Cut of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. I had no idea.

This fabled purse seiner, hull packed with memories of Monterey and Baja, had been docked mere walking distance from my Seattle home, having her insides tenderly rehabilitated by the capable hands of my good friend Rob while I edited a screenplay filled with scenes of Steinbeck and Ricketts laughing on her deck, enjoying that “feeling of fullness, of warm wholeness…wherein every experience seemed to key into a gigantic whole.” What were the odds of such a meaningful coincidence? I certainly felt keyed into the gigantic whole now.

Rob put me in touch with Chris, setting me up to attend the Western Flyer’s departure party in Monterey and to meet all of the other amazing members of the Western Flyer Foundation. There, I again experienced that quiet reverence I first felt in Doc’s lab as a boy. This time, the memory remains clear and always will.

Walking through the belly of that boat, smelling the salt air of the sea from her bow, looking up to the crow’s nest at the giant stag antlers watching over Monterey Bay like ancient sentinels, seeing for myself all those sights I’d toured innumerable times in my mind’s eye, it struck me that I was not aboard some floating museum dedicated to the memory of a single expedition sailed nearly a century prior. I was on a living, breathing research vessel that was alive with hopes and dreams for the coming generations, a boat filled with the fire of a “man-shaped soul.” This boat was not anchored in the past, but set full-steam ahead to the future.

As the Western Flyer and her crew prepared to retrace her renowned Baja expedition on that sunny March day, eighty-five years to the week after Steinbeck and Ricketts’ famed voyage, on the birthday of both Carol Steinbeck and the Western Flyer Foundation’s fearless director Sherry Flumerfelt, the sea sparkled with sunlight. “Sea lions barked with a tone that would have gladdened the heart of St. Francis,” as Steinbeck said in Cannery Row. Children and the elderly looked on with wonder and somewhere, the spirits of John and Ed and Carol and Captain Berry and Sparky and Tiny and Tex smiled down with pride and toasted John Gregg for a fine job well done.

Watching the Flyer shrink into the bay, I felt connected to everything around me, the people, the wildlife, the wind and the waves, the spirit of my father and his father before him. I hugged my Aunt Stacey, thanked her for introducing me to the world of Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck so many years ago, and we settled into that “golden emotion” of leave-taking, waving bon voyage to the crew brave and foolhardy enough to follow in the footsteps of legends.

The Western Flyer dwells at the intersection of science and story, where deeply rational thought converges with mystic wonder. Hers is an endlessly fascinating story and a reminder that we never know what treasures lurk beneath the surface. Every human being, every plant, every animal; we are all living, breathing stories, overlapping in endless fractals, an Indra’s net reflecting itself into eternity, stars and glittering pearls and the tickling tendrils of anemone orbiting one another in the delicate dance of infinity. One must only have the courage to ask questions of their surroundings, the curiosity to quietly observe, and the time to contemplate the answers. I am grateful that the Western Flyer Foundation has made this their mission, to ignite this flaming passion for learning and storytelling in generations to come.

May the Western Flyer continue to sail into the annals of history and leave a legacy as bright as her most famous passengers. Here’s to another eighty-five years!

“Our Father, who art in nature.”

Amen.

Publicado en Blog, Stories from the Community