By Nick Rahaim

The Western Flyer was underway in frigid Alaskan seas, taking on water faster than it could pump it out. It was 1964, and the 76-foot wooden vessel had just been refitted with an aluminum crab tank for the lucrative king crab fishery on the Bering Sea. The new tank cracked, and thousands of gallons of water—held for ballast—poured into the hull, flooding the engine room. The captain placed a mayday call to the United States Coast Guard after pumps failed and the boat began to slowly sink.

An aircraft came to the rescue and dropped additional pumps onto the bow. The captain and crew were able to remove the water and stabilize the boat. But just as the situation settled down, smoke and the smell of burning emanated from inside the cabin. Upon investigation, the cook was discovered in the galley cooking steaks. “If we are gonna go in the water, we are gonna go in with a full stomach,” he told the stunned captain.

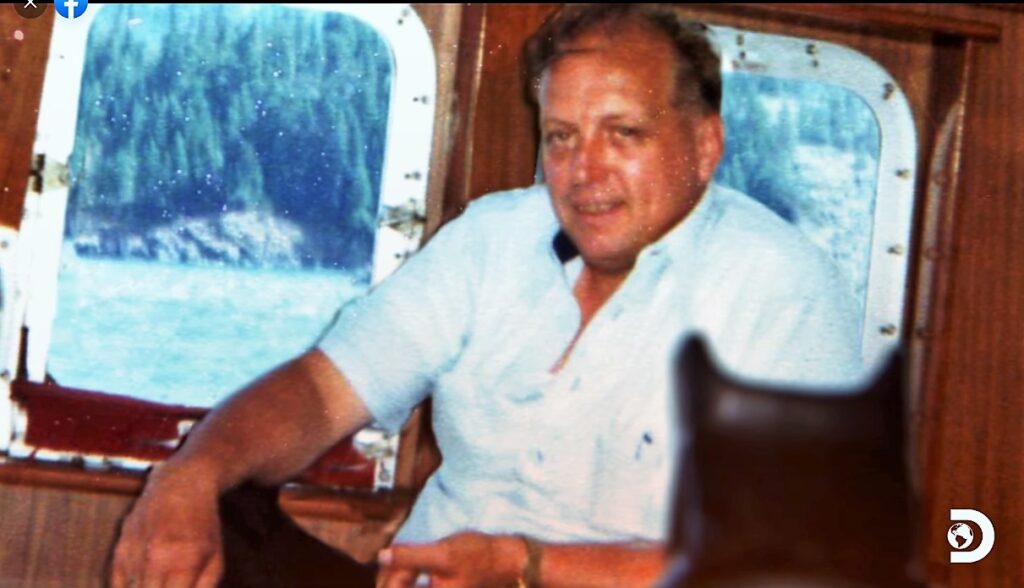

That cook was the Norwegian-born Sverre Hanson (father of Sig Hansen, captain of the F/V Northwestern, made famous by his role on the popular Discovery Channel reality TV series The Deadliest Catch). The elder Hansen crewed on the Western Flyer in the 1950s and 1960s when it was a highliner in the Seattle fleet. But he was just one deckhand among dozens of others, over more than half a century, who lived and worked on the vessel.

As retired marine biologist and author of the 2015 book The Western Flyer Kevin M. Bailey notes, the key to the Flyer’s history is adaptability. While John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts’ sojourn into the Gulf of California on a six-week expedition in 1940 brought fame to the Western Flyer, its decades-long journey as a commercial fishing vessel is no less important to its story. It’s a tale that not only chronicles the ecological and economic history of North Pacific fisheries in the 20th century—booms, busts, and all—but also the tradition and the indomitable spirit of fishing communities.

Cashing in on sardines

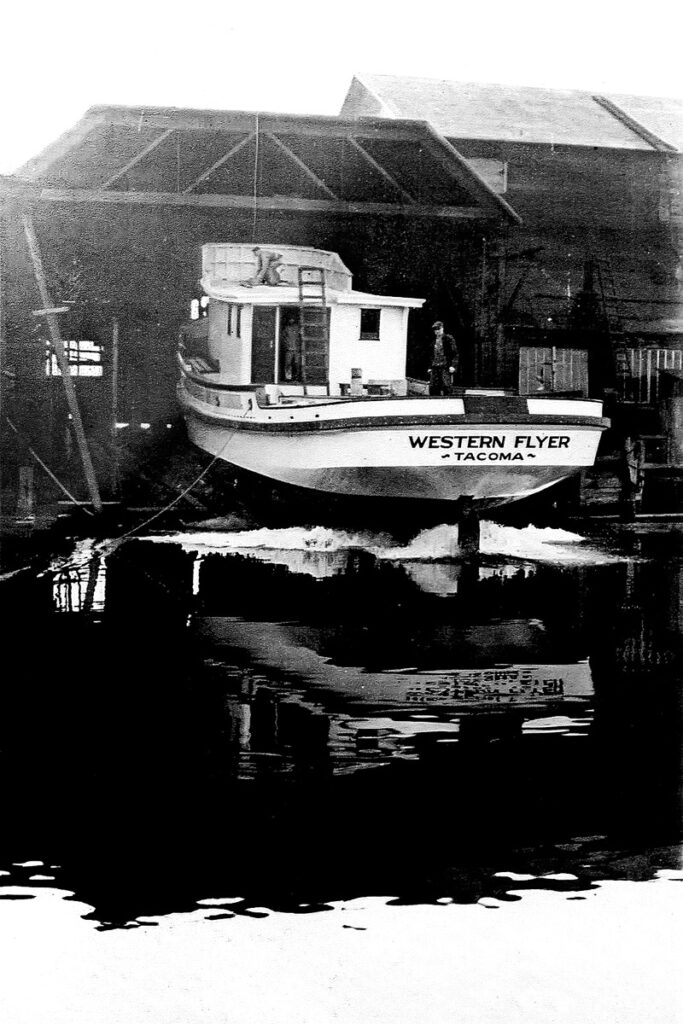

Originally made as a state-of-the-art sardine seiner by Western Boat Building in Tacoma, Washington in 1937, the Western Flyer’s story goes back to fishing villages on the coasts of Sicily, Croatia, and Norway. Mid-century fisheries of the West Coast were largely developed by immigrants from these countries, who adapted old-world know-how to the Pacific. In fact, it was a shipwright from Croatia named Martin Petrich who built the vessel in partnership with a fellow countryman, Frank Berry, and his son Anton. The younger Berry—born and raised in the Pacific Northwest—married into a Sicilian fishing family in Monterey.

When the boat was complete, Anton “Tony” Berry piloted the Western Flyer out of Puget Sound south to Monterey for sardines, but not before a short stop at the Columbia River to fish salmon. Over the next year, the vessel covered more than 10,000 miles of ocean, from Bristol Bay off the Bering Sea in Alaska for a U.S. Bureau of Fisheries salmon survey and then down to Baja California for tuna—a long journey for a boat whose cruising speed was less than 10 knots per hour.

Berry finally settled in Monterey to focus on sardines and to be close to his wife, Rose, of the Enea family when sardines were at their peak, and Monterey was one of the most valuable fishing ports in the world. When Steinbeck and Ricketts hopped on the Western Flyer for their leisurely 1940 journey, they found a Mediterranean mix of Croatian-American and Italian-American fishermen including Berry at the helm, his brother-in-law Horace “Sparky” Enea, and Ratzi “Tiny” Coletto. Rounding out the crew was a Texan named Hall “Tex” Travis and Steinbeck’s wife Carol.

While the six-week trip to the Gulf of California lingers long in the public imagination of the Western Flyer, it would be just a blip in the history of the fishing boat—especially to those whose livelihoods depended on it.

The Puget Sound Years

After sardines went bust, Berry sold the Western Flyer back to boatbuilder Petrich in 1948. It changed hands again when it was sold to Armstrong Fisheries in Ketchikan, Alaska, to harvest herring before being sold once more to Dan Luketa, another fisherman of Croatian heritage, in 1952. As it was passed from owner to owner, the story of the two eccentric friends with dubious morals was not.

“In its day, the Western Flyer was famous, but not for what Steinbeck did on it,” said Hal Hines, who worked three summers on the boat as a high schooler in the late 1950s. “It was absolutely the queen of the fleet, top dog, made the most money…but no one had any idea it was famous outside of fishing.”

Luketa converted the Western Flyer into a trawler to jump on the lucrative ocean perch fishery. It would also catch petrale sole, Pacific cod, and other groundfish. To capture bottom-dwelling fish, such a trawler uses a funnel-shaped net, similar to a windsock, that sets around 300 fathoms deep and tows along the ocean floor with two heavy-duty, half-mile long tow cables.

Luketa was an innovative fisherman, always looking for ways to improve equipment and procedures to fish more efficiently and earn more money. He had patented “doors” that held the trawl net open, using the flow of water like a sail uses wind, that would become standard for trawl operations the world over. Luketa was also a hard driver, forcing his crew to work around the clock until the fish hold was stuffed. Then there would be no sleep on the ride back to port until the Western Flyer was spotless.

“You always made money with him,” Sverre Hanson said of him, as quoted in the book The Western Flyer.

One day in the 1950s, the newly-immigrated, broke, and unemployed Hanson went out to buy a bottle of fortified wine in the Seattle neighborhood of Ballard. He ran into Luketa, who was in need of crew after two deckhands quit, possibly over the grueling work and lack of sleep. The job Luketa offered Hanson forever changed the trajectory of his life.

Hines got his chance to work aboard the Western Flyer in a different way. His father was a fisherman from Seattle but decided to change professions and take his family to Southern California after he came back from World War II with lasting battle injuries. But he didn’t lose his connections and secured his son a summer job on the Western Flyer through a contact. Hines took a bus up to Bellingham, Washington, to meet Luketa as he pulled in to offload fish. When a seafood buyer told Luketa about the crewmember-in-waiting, the captain had completely forgotten that he had agreed to take him on for the summer. Dismayed but undeterred, Hines hung around the dock, hoping there would be another boat in need of a greenhorn.

When the Western Flyer did pull up, Hines saw a red-faced Luketa—who was known for his fierce temper and profanity-laden tirades—screaming at the seafood buyer over the price of fish. But even amidst the tantrum, the buyer learned that a deckhand had gotten seasick and stayed in his bunk for eight days straight and Luketa promptly fired him when the Western Flyer made it to its home port in Seattle. The buyer then told Hines to gather his things, immediately hitchhike to Seattle Ship Supply, and ask Luketa for a job.

Luketa was initially skeptical of the youngster but agreed to hire him if he could be ready to leave in three hours. Since Hines lacked gear, Luketa had an experienced deckhand help outfit him at Seattle Ship Supply on his tab. In that first summer, Hines had work like he never had before, “screwed up a bunch of times,” but had learned the job and was offered a spot the following summer. He went home with a check for $1,800, an equivalent to around $20,000 today, and enough to buy himself a Chevrolet Bel Air when he returned to California.

“Luketa would scream at you. He was a hard-driven guy and allowed absolutely no questions on the water,” Hines said. “But I just loved it. I loved everything about it.”

But like sardines the decade before, the bottom was dropping out of the groundfish fishery in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1960s. At that time, there was no 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) to protect US fish stocks from foreign fishing vessels. The Japanese and Soviets legally operated their industrial ships up to the territorial limit three miles off the coast. Nineteen sixty-five marked the height of the foreign fishing effort off the West Coast, with non-US-flagged vessels landing 15,000 metric tons of ocean perch, nearly four times greater the amount than US boats, according to Bailey.

“The Soviet fleets could easily reduce the fishery stocks off the coast to the extent West Coast fishermen may not be able to catch enough fish to stay in business,” Luketa said, according to Bailey’s The Western Flyer.

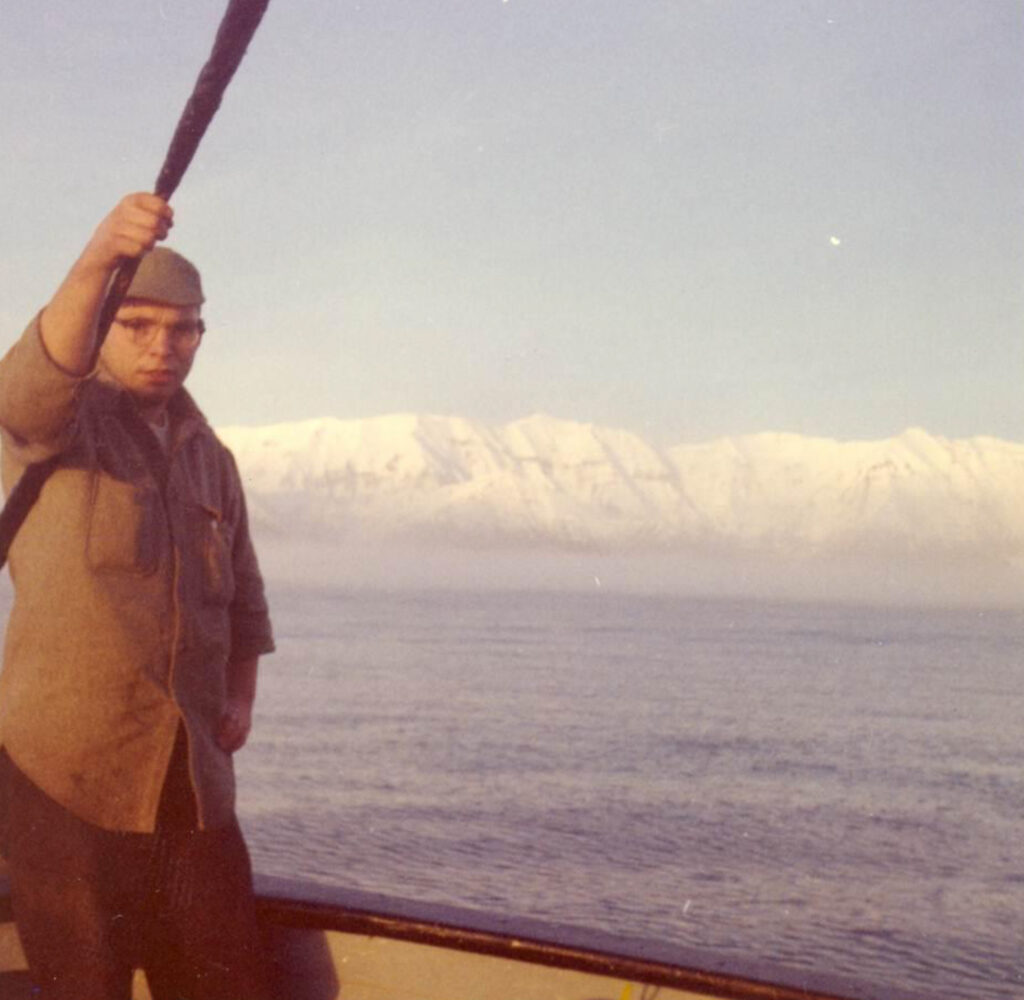

With the once-prosperous fishery in decline, Luketa chartered the Western Flyer to the International Halibut Commission to conduct trawl surveys on the Gulf of Alaska in 1962. The bilateral commission between the US and Canada was trying to assess the impact of foreign fleets on the Pacific halibut stocks. Colin Levings, a young Canadian oceanographer-in-training, secured a job on the survey crew to pay his way through college at the University of British Columbia. He wouldn’t work for the legendary Luketa, who had hired a skipper to run the boat.

Levings worked on the Western Flyer for two years and was unaware of the boat’s connection to Steinbeck and Ricketts. It wouldn’t be until he visited Monterey’s Cannery Row in 2001 that he made the connection when he saw a copy of the Log of the Sea of Cortez for sale with a photo of the boat on the cover. He documented his years on the Western Flyer with a 2016 memoir, “Chiefly between Kodiak Island and Cape Spencer, Alaska.”

Death and Danger in Alaska

Levings would have stayed on the Western Flyer for the 1964 trawl survey season, but Luketa decided to join the next fishing bonanza and retooled the boat for Alaskan king crab. As fate would have it, Levings was on a different trawl survey vessel motoring across the Gulf of Alaska that year when a distressed boat loaded with king crab pots was spotted. It was the Western Flyer, bobbing in the swell, with a panicked crew on deck and Sverre Hanson frying steaks in the galley. Levings snapped a photo before his vessel moved on after help came from the Coast Guard.

“She could have been a goner if they hadn’t gotten the pumps from the plane,” said Levings.

Though everyone lived to tell the tale, the Western Flyer had flirted with real disaster. In 1964, fishing for crab in Alaska was legitimately the deadliest fishery in the United States, a distinction it lost by the time of The Deadliest Catch series, in spite of the title.

In the late 1960s, Luketa hired a real-life Captain Hook named Jackie Ray to run the Western Flyer in Alaska. According to Bailey, Ray had lost his hand in a fishing accident when it was caught in the bite of a drum hauling in cable, replacing it with an “iron claw”. Ray was known as a boozer and a brawler who had wrecked a few boats; he was intimidating in a quiet way, with an awkward laugh, and was a man who drove his crew hard and received their ire for it.

One day, while the Western Flyer was crab fishing in the Aleutian Islands, Ray was unhappy with the way his crew was setting pots. He emerged from the wheelhouse, jumped on deck, and set the 700-pound crab trap, but his hook caught fast, and he began to slide across the deck in his rubber boots. The metal cage pulled him overboard and down into the dark sea.

The crewmembers were able to turn the boat around, grapple the buoy line, and pull the pot to the surface. Ray emerged pale, limp, and lifeless…but his body slipped away from the prosthetic hand and he descended into the deep, dark water, never to be seen again.

There are different versions of this story. Sig Hansen wrote in his memoir, North by Northwest, that the crew of the Western Flyer that day might have “given him a little help to the bottom.” Bailey also recounts an alternative version of the story where Ray was stuffed in a crab pot and set overboard with no buoy line. “They left that pot there as Jackie’s casket,” he wrote.

There was another time when the Western Flyer inadvertently became a whaler. In 1966, according to the 2019 book Cannery Row: The History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue by Michael Kenneth Hemp, a Minke whale became entangled in the buoy line of a crab trap and drowned. The boat was skippered by two Aleut brothers who had the whale hauled aboard—a process that took hours—before bringing it to King Cove and feeding the community for several days during a Christmas celebration. Whale entanglements continue to be a challenge to this day, imperiling the lives of whales and the livelihoods of fishermen.

Just as sardines and ocean perch before, the king crab fishery off the Aleutian chain went bust after too many boats attempted to cash in on a finite resource. The fishery was still productive in the eastern Bering Sea, but as an old sardine seiner, the Western Flyer proved to be too small and too slow. Luketa purchased the F/V Apollo and sold the old wooden vessel he had skippered for nearly two decades.

The Gemini Days

When Whitney-Fidalgo Seafoods purchased the boat, it was no longer the Western Flyer. The year prior, in 1970, Luketa renamed the vessel Gemini, after NASA’s space program. The name change further disconnected the vessel from its literary roots with Steinbeck and Ricketts, but its life at sea would continue, albeit at a slower clip.

In 1971, the boat was a salmon tender in Southeast Alaska. While underway and loaded with 120,000 pounds of salmon, the Gemini struck a reef outside of Ketchikan. The Coast Guard rescued the crew, but considered the vessel to be “a total loss” during the on-site inspection. The keel was broken, but a diver was able to patch the hull and refloat the boat. The vessel would never be the same, but would continue to work as a tender and crabber in the North Pacific for the next 15 years under multiple owners.

“I’ll never forget when that boat came into harbor,” said Dennis Fry, whose family owned the boat in the mid-1970s. “I was on the Homer Spit and I said ‘look at that, that’s a pretty boat.’”

Fry’s family operated the Gemini out of Homer, Alaska, and ran it as a salmon tender in Cook Inlet and as a crabber for Dungeness and tanner crab on the Gulf of Alaska. While aging, Fry said the Gemini was “still one of the best boats out there” and held up in a particularly bad storm outside of Valdez, Alaska when the ocean spray turned to ice in the freezing conditions, making it dangerously top heavy.

Eventually, a marine biology student working as a deckhand told him that the Gemini was once the Western Flyer made famous by a Nobel Prize-winning author, but Fry didn’t pay much attention. In retrospect, he’s impressed with the long journey of the Western Flyer. “That boat’s been around, boy!”

The family sold the boat back to Whitney-Fidalgo Seafoods in the early 1980s, Fry said, before being sold again to a fisherman in Anacortes, Washington.

Return of the Western Flyer

The Gemini remained in Anacortes harbor for the next two decades. With planned restorations put off, the old vessel aged out of its working life, sinking at its moorings in a shallow slough by a casino in 2012. Though refloated, it sank again while on anchor in 2013 and remained on the seafloor for five months before it was lifted to the surface again and towed to Port Townsend, where it could be restored on a dry dock.

Bob Enea, nephew of Sparky Enea and Tony Berry, kept a close eye on the Gemini for decades after he was able to track it down to Anacortes in 1986. In the early 1990s, he created a nonprofit, the Western Flyer Project, to raise funds to purchase it but a Salinas developer bought it before he could (John Gregg later bought the Flyer from the developer, but that’s a story for another day).

“It was my uncle’s boat and it’s pretty famous and worthy of being preserved,” Enea said. His large Italian family would meet after church every Sunday, he said, but when the old fishermen would begin telling tales of their time on the Western Flyer the kids would be sent outside to play. These stories would go the way most fish stories go—out with the tide of time.

But for Enea, it’s not the specifics—the near-death experiences, the good times, the arguments, and the blood, sweat and tears of a colorful crew of characters that manned the Western Flyer over the years—it’s the fishing tradition that’s important to preserve and celebrate.

Nick Rahaim is a California-based writer, science communicator, and erstwhile commercial fisherman. Check out his website at www.outside-in.org.

Posted in Blog