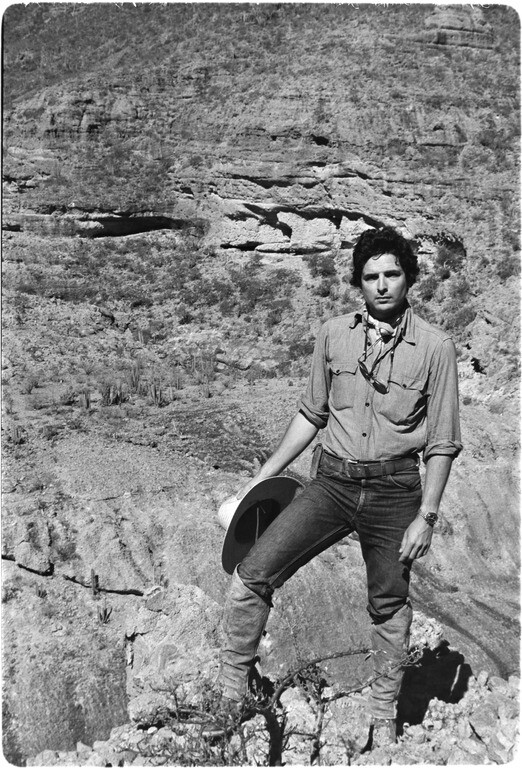

When Enrique Hambleton first read The Log from the Sea of Cortez, he was swept away by the book’s combination of art and science. This blend has been the hallmark of his own career, which spans everything from ocean conservation activism to the analysis and preservation of Baja California cave art. As a member of the Western Flyer Foundation Board since 2020, Enrique recently shared his story and insights on how it connects to the Western Flyer’s historic return to the Gulf of California next spring.

From Cave Paintings to Conservation

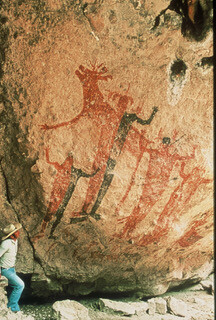

Enrique’s long commitment to cave art came about almost by accident. “Back in 1971,” he remembers, “I was working on an article on the peninsula of Baja California for National Geographic. And I was taken to visit a cave painting site—prehistoric cave paintings. And I asked our guide, are there any more of these paintings? And he said, Oh yes, they’re everywhere. And I said, are you kidding? He said, No, no, hundreds. And I said, I’ll be back!”

He returned six months later. The paintings had been reported upon before—by 18th century Jesuit missionaries, by a 19th century French chemist, then in a Life Magazine article by Erle Stanley Gardner—but nobody had ever done more than basic description. Enrique threw himself into the project with gusto. “I discovered not only the beauty and magnificence of prehistoric rock art in Baja California but that it existed in a natural environment,” he says. It was a combination of geology, chemistry, and deep-time human art that recalled his readings from the Log. “I haven’t been able to articulate it as beautifully as Steinbeck and Ricketts did,” he says. “But the intersection of art and science came to me as a result of trying to conserve prehistoric rock art.”

He had a thousand questions. “What does the rock consist of? Why is it deteriorating? Can anything be done to mitigate that? And then [there’s] the art itself, which is a magnificent expression by hunters and gatherers about their world 10,000 years ago. Where they lived, what they hunted, what they believed. The paintings are a bridge, if you will, between the spoken traditions and the written ones.”

It was like being in a vast botanical garden that contained one of the largest concentrations of prehistoric art on earth but one that was in slow, inevitable decline. The geologic and seasonal forces slowly deteriorating the artwork made its beauty more poignant. “Is there anything we can do? Very little,” he says with a degree of resignation—he understands as well as anyone the science that makes the damage inevitable. “What does the rock consist of? What happens to water when it percolates down the mountain? What happens when that water dissolves salts? What happens to those salts when they gravitate to the surface and crystallize?”

He answers his own question. “Boom–they bump off, and they pop off little bits and pieces of the canvas, which is a constant process. 50,000 years from now, those paintings will probably be gone. And there’s nothing we can do about it, because they’re porous, volcanic mountains. You can divert water and define the drip line. But it’s a losing battle.

“Looking at it holistically, it’s not just a painting on the face of a rock,” he reflects. In Enrique’s view, conservation requires seeing the totality of a thing, of the object and the forces acting upon it and its past and its future all combining in a single important whole. “All of it,” he says. “It’s basically what Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck came up with. Either everything is connected or nothing is–and everything is connected.”

Breaking the Cycle in Fisheries

The same ethos drives Enrique’s work in environmental and fisheries conservation. He is one of the founders of two organizations, the Baja California Sur focused Niparajá and Pronatura Noroeste, which is based in Ensenada and covers six states in Northwest Mexico—both share a focus on marine conservation…and its vital importance for human thriving. Unfortunately, given the pressures of life around the Gulf the need for conservation can take a back seat to the immediate need for survival.

“Right now fishing communities are stuck in a vicious cycle,” Enrique says; the fact that some fishers ignore regulations creates pressure for everyone to do so. “A fisherman told me very pointedly once, sitting at the table in his little house in a fishing camp, I know what I’m doing is wrong. He was talking about overfishing and fishing out of season. I know that what I’m doing is wrong, but I have to put food on the table for my family. And I know that that means hunger for all of us tomorrow. So he’s being forced to do something illegal because [of what] his neighbors are doing and they’re taking all the fish.”

To break that cycle, both organizations work to create no-fishing zones throughout the Peninsula of Baja California and its Gulf; smaller than California’s Marine Protected Areas, they rely on deeply connected locals rather than the navy or coast guard for protection. Local communities, Enrique says, are “the ones that go diving and check and make sure that traps haven’t been set, that nets have not been deployed, that boats are not coming in surreptitiously in the middle of the night and fishing.”

“There was, and still is, a great deal of corruption on the part of the three levels of government to allow illegal fishing because of bribery. [All of that] drives me to make sure that we do a good job in empowering these disenfranchised fishermen to protect their heritage and their livelihood. It’s their fish, at the end of the day.”

The Western Flyer: A Messenger for the Gulf

Today, Enrique is excited about the Western Flyer’s upcoming return to the Gulf and to communities Steinbeck and Ricketts visited nearly 85 years ago. “It’s a really beautiful gesture, the Flyer going back as a messenger [so long after] its first trip in 1940,” he reflects. “It’s going to visit underserved fishing communities in the Gulf of California. It’s going to go to the places where Steinbeck and Ricketts went. So it’ll be a good opportunity for science to see what has changed in those places. Is it the same? Is it better? Or is it worse? And [we’ll] share that with the communities.”

What the Flyer will find remains to be seen—but there’s no doubt that, like the cave paintings of Baja California, the ocean life of the Gulf is under significant strain.“I’m afraid it’s not going to be good news,” Enrique says. “The Gulf of California is in big trouble for a number of reasons; pollution from the mainland rivers with toxins and fertilizers and effluents from cities, from neglect, from corruption, from impunity, the lack of the rule of law, from illegal fishing.

Fortunately, some of the places that the Flyer is going to go to on this first journey may be a little more resilient because they’re isolated. They haven’t yet felt the impact. However, the Gulf of California is really quite small, and very susceptible to human activity.”What’s more, the passage of time—and the fact that the Log’s Spanish translations have been limited—means that many Baja California locals have yet to hear the Flyer’s story. Enrique hopes that the return voyage will change that. After all, the boat’s full restoration has made it uniquely well suited to gathering information on the current state of the Gulf, having a shallow draft, a quiet engine, and a full set of state-of-the-art instrumentation. It’s an inspiring rebirth; perhaps the most important message of the trip is the existence and resilience of the Flyer itself.

Posted in Blog