By Eric Rankin

After my first reading of The Log of the Sea of Cortez in the mid 1970s, I became intrigued – some would say slightly obsessed – with marine biologist Ed Ricketts, the inspirational muse not only to novelist John Steinbeck, but also to mythologist Joseph Campbell. Without Ricketts, there would have been no “Doc” in Cannery Row or, quite possibly, no premise of a global “mono-myth” as Ricketts wrote about in a one-page dissertation, and which you may be more familiar with as Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey.”

Though these three men spent time together in the 1930s philosophizing, reading, drinking and carousing together in the Monterey area, I believe it was the impact of two different tide-pooling expeditions that permanently cemented the legacy of Edward Flanders Ricketts into the minds and hearts of both Steinbeck and Campbell.

Of course, to embark on any type of marine expedition, a boat becomes the most essential piece of equipment needed for the trip. In 1932, that boat was a small launch named Grampus, which ferried Ricketts and Campbell north through the inside passage to Alaska. Eight years later in the spring of 1940, it was the Western Flyer, a stout and capable purse seiner based in Monterey that transported Steinbeck, Ricketts, and a small crew into the Sea of Cortez for a 6-week charter to explore the intertidal regions of the Gulf of California. While there, they discovered and named many previously unknown animals living in the littoral zone, pondered the holistic interconnectedness of life in the tidepool environment, drank gallons of Carta Blanca beer, and fished and laughed all the while.

Eventually, however, the trip proved to be something much bigger to each of them. As if they were studying their own lives the same way a marine biologist studies a specimen under a microscope, they began to feel into the interconnectedness not only of the little animals living in the tidepools, but to the interconnectedness of… everything. And while Steinbeck never made a single entry into the ship’s log during the charter, Ricketts scribbled down some of the most profound philosophical observations I have ever read. He came to realize that the micro often reveals the macro of any system, that one thing was never separate from the whole thing, and that is-ness was the most important concept to grasp whether pondering the smallest marine invertebrate or the entire universe. One may never know the why, or the how, or the projected meaning of anything, but we can all observe, address, and choose our reaction to what is in every new moment.

After the charter, Western Flyer went back to work as a seiner and occasional research platform plying the waters from California to Alaska. When her name was changed to Gemini, the trail grew cold as to her whereabouts, or if she was even still afloat. That all changed in 2015 when the Flyer, now a dilapidated hulk that had indeed sunk numerous times, was rescued by an avid fan of the book Steinbeck himself considered to be his best work. Acting upon what many considered an irrational desire to not only restore the boat, but to repurpose her as a state-of-the-art research vessel to be used by children and credentialed scientists alike, John Gregg paid a million more times her worth. In other words, he bought a worn-out, water-logged, barnacle-encrusted wreck of a boat for a million dollars.

When I became aware that the Flyer was destined to become a seaworthy vessel once again, (a process that took nearly a decade and many more millions of dollars to complete,) I knew the day would come when I would see her for myself. Maybe she would be docked beside one of the canneries in Monterey and I would get nothing more than a photo from afar, but one way or another, I would lay eyes on the boat from which thousands of philosophical conversations and a multi-layered, life-changing book had been launched.

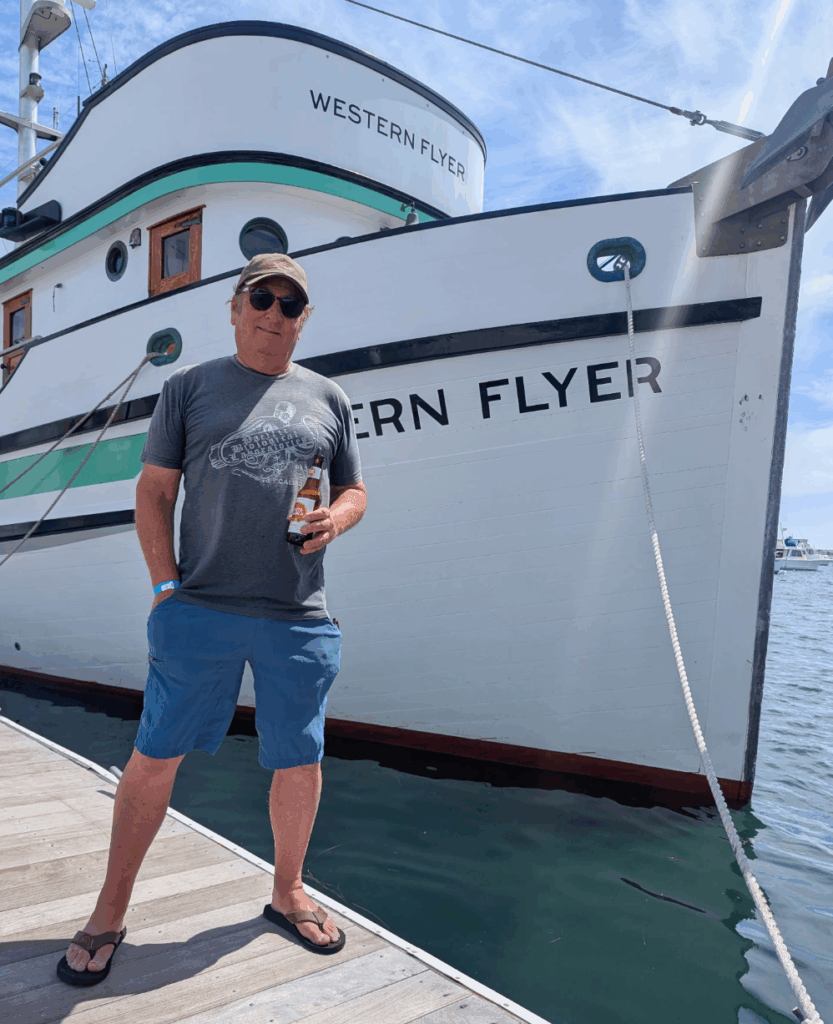

To my utter astonishment, after completing her first return trip to Baja in the spring of 2025, the Flyer and her crew found their way north to a wooden-boat festival in Newport Beach, California, less than five miles from where I live! I will never forget that day: the rush of excitement to not only board her, but to be led on a private tour by rescuer John Gregg, to be gifted a piece of wood from one of the Flyer’s original ribs, to sip a Carta Blanca beer with Sherry Flumerfelt, executive director of the Western Flyer Foundation.

Two weeks have gone by since boarding this almost mythical legend of a boat, and I am still buzzing with excitement, gratitude, and even a degree of disbelief. As I relive the moments of running my hands over her rails, sitting at the dinette where many enlightening conversations took place over 85 years ago, looking out through the pilothouse, I can feel her influence on the thinking of Ricketts and Steinbeck and probably even Joseph Campbell. For it was on this boat that the words, “It would be wise to look into the tidepool, then up to the stars, then back to the tidepool again” were written.

If there is a more elegant and concise way to say that “one thing is connected to everything, and everything is connected to one thing,” I have yet to read it.

Eric Steven Rankin is an author and researcher exploring the intersection of ancient cultures, religion, physics, and sound. His groundbreaking work connecting geometry and musical harmonics has been featured on the History Channel, Gaia TV, and in numerous scientific forums.

Eric was kind enough to kick off our new question to the community: What does the Western Flyer mean to you? You don’t need to be a researcher or author—we want to hear from everyone. Whether it’s a memory, a feeling, or a favorite moment, big or small, we’d love to hear from you.

Posted in Blog, Stories from the Community